1902 Encyclopedia > Mural Decoration > General Schemes of Mural Painting

Mural Decoration

(Part 15)

PAINTING AND MURAL DECORATION (cont.)

General Schemes of Mural Painting.

General Schemes of Mural Painting.— From the 11th to the 16th century the lower part of the walls, generally 6 to 8 feet from the floor, was painted with a dado—the favourite patterns till the 13th century being either a sort of sham masonry with a flower in each rectangular space (fig. 10), or a conventional representation of a curtain with regular folds stiffly treated (Plate I.)

Fig. 10 -- Wall-Painting of the 13th century. "Masony pattern."

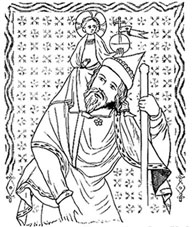

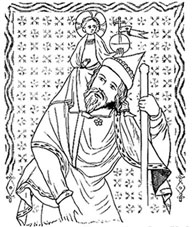

Above this dado ranges of pictures with figure-subjects were painted in tiers one above the other, each picture frequently surrounded by a painted frame with arch and gable of architectural design. Painted bands of chevron or other geometrical ornament till the 13th century, and flowing ornament afterwards, usually divide the tiers of pictures horizontally and form the top and bottom boundaries of the dado. In the case of a church, the end walls usually have figures to a larger scale. On the east wall of the nave over the chancel arch there was generally a large painting of the "Doom" or Last Judgment. One of the commonest subjects is a colossal figure of St Christopher (fig. 11), usually on the nave wall opposite the principal entrance, —selected because the sight of a picture of this saint was supposed to bring good luck for the rest of the day. Figures were also often painted on the jambs of the windows and on the piers soffit of the arches, especially that opening into the chancel.

Fig. 11 -- Wall Painting of St Christopher. Large life-size.

The little Norman church at Kempley in Gloucestershire (date about 1100) has perhaps the best-preserved specimen of the complete early decoration of a chancel. [Footnote 45-1] The north and south walls are occupied by figures of the twelve apostle in architectural niches, six on each side. The east wall had single figures of saints at the sides of the central window, and the stone barrel vault is covered with a representation of St John’s apocalyptic vision—Christ in majesty surrounded by the evangelistic beasts, the seven candlesticks, and other figures. The chancel arch itself and the jambs and mouldings of the windows have stiff geometrical designs, and over the arch, towards the nave, is a large picture of the "Doom." The whole scheme is very complete, no part of the internal plaster or stone-work being undecorated with colour. Though the drawing is rude, the figures and their drapery are treated broadly and with dignity. Simple earth colours are used, painited in tempera on a plain white ground, which covers alike both the plaster of the rough walls and the smooth stone of the arces and jambs.

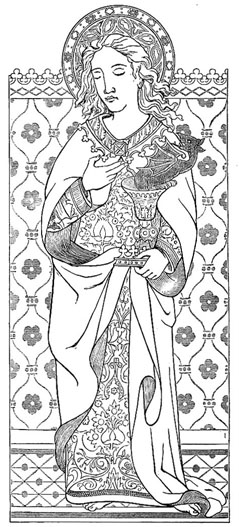

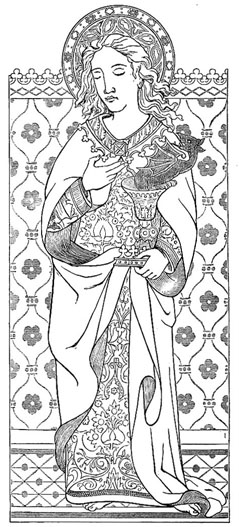

In the 13th century the painters of England reached a very high point of artistic power and technical skill, so much so that at that time paintings were produced by native artists quite equal, if not superior, to those of the same period anywhere on th Continent, not excepting even Italy. The central paintings on the walls of the chapter-house an on the retable of the high altar of Westimister Abbey are not surpassed by any of the smaller works even of such men as Cimabue and Duccio di Buoninsegna, who were living when these Westminster paintings were executed. Unhappily, partly through the poverty and anarchy brought about by the French wars and the Wars of the Roses, the development of art in England made but little progress after the beginning of the 14th century, and it was not till a time when the renaissance of at in Italy had fallen into a state of degradation and decay that its influence reached the British shores. In the 15th century some very beautiful and noble work, somewhat affected by Flemish influence, was produced in England (fig. 12), chiefly in the form of figures painted on the oak panels of chancel and chapel screens, especially in Norfolk and Suffolk; but, fine as many of these are, thy cannot be said to rival in any sense the works of the Van Eycks and other painters of that time in Flanders.

Fig. 12 -- 15th century English painting -- St John the Evangelist.

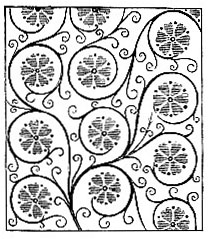

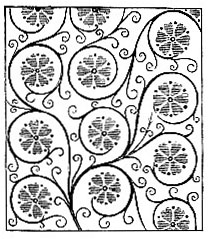

To return to the 13th century, the culminating period of English art in painting and sculpture, much was owed to Henry III.’s love for and patronage of the fine arts; he employed a large number of painters to decorate his various castles and palaces, especially the palace of Westminster, one large hall of which was known as the "painted chamber" from the rows of fine pictures with which its walls were covered. After the 13th century the "masonry pattern" was disused for the lower parts of walls, and the chevrony and other stiff patterns for the borders were replaced by more flowing designs (Plate I.). The character of the painted figures became less monumental in style; greater freedom of drawing and treatment was adopted, and they cease in any way to recall the archaic majesty and grandeur of the Byzantine mosaics. A detailed description of the development of the successive styles of mural painting would be almost a complete history of English art, which space does not allow here, but it may be noted that during the 14th century wall-spaces unoccupied by figure-subjects were often covered by graceful flowing patterns, drawn with great freedom of hand and rather avoiding geometrical repetition. Fig. 13, from the church of Stanley St Leonard’s, Gloucestershire, is a good characteristic specimen of 14th century decoration; it is on the walls of the chancel, filling up the spaces between the painted figures; the flowers are blue, and the lines red on a white ground.

Fig. 13 -- Flowing Pattern; English 14th Century Wall-Painting.

In some cases the motive of the design is taken from encaustic tiles, as at Bengeo Church, Herts, where the wall is divided into squares, each containing an heraldic lion. This imitative notion occurs during all periods—masonry, hanging curtains, tiles, and architectural features such as niches and canopies being very frequently represented, though always in a simple decorative fashion with no attempt at actual deception, —not probably from any fixed principle that shams were wrong, but because the good taste of the mediaeval painters taught them that a flat unrealistic treatment gave the best and most decorative effect. Thus in the 15th and 16the centuries the commonest forms of unpictorial wall-decoration were various patterns taken from the beautiful damasks and cut velvets of Sicily, Florence, Genoa, and other places in Italy, some form of the "pine-apple" or rather "artichoke" pattern being the favourite (fig. 14), a design which, developed partly from Oriental sources, and coming to perfection at the end of the 15th century, was copied and reproduced in textiles, printed stuffs, and wall-papers with but little change down to the present century, —a remarkable instance of survival indesign.

Fig. 14 -- 15th Century Wall-Painting, taken from a Genoese or Florentine velvet design.

Fig. 15 is a specimen of 15th century English decorative painting, copied form a 14th –century Sicilian silk damask. Diapers, powdering with flowers, sacred monograms, and sprays of blossom were frequently used to ornament large surfaces in a simple way. Many of these are extremely beautiful (fig. 16).

Fig. 15 -- 15th Century Wall Painting, the design copied from a 13th Century silk damasc.

Fig. 16 -- Powderings used in 15th century Wall-Painting.

|