1902 Encyclopedia > Nineveh

Nineveh

NINEVEH (Hebrew ___, in classical authors Nivos, Ninus; LXX., Jerome, Niniue), the famous capital of the Assyrian empire, called Ninua or Nina on the monuments.

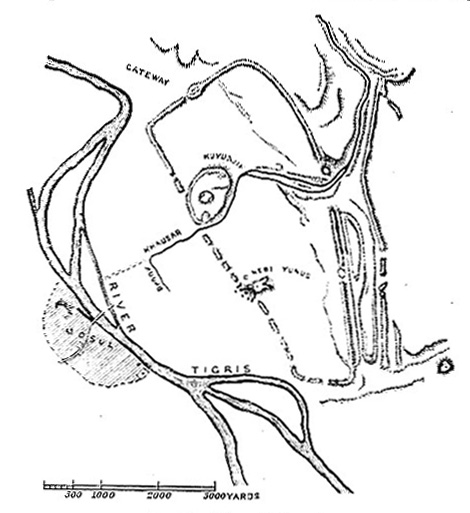

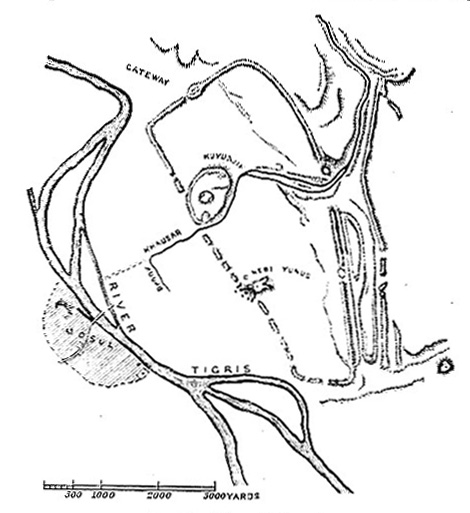

Through the city appears to have been entirely destroyed in the fall of the empire (Footnote 511-4) the name of Nineveh (Syriac, Ninwe; Arabic, Nínawá, Núnawá) continued, even in the Middle Ages, to be applied to a site opposite Mosul on the east bank of the Tigris, where gigantic tells or artificial mounds, and the traces of an ancient city wall, bore evident witness of fallen greatness (Footnote 511-5).

The walls enclose an irregular trapezium, stretching in length about 2 1/2 miles along the Tigris, which protected the city on the west.(Footnote 511-5) The greatest breadth is over a mile. The most elaborate defenses, consisting of outworks and moats that can still be traced, were on the southern half of the east side, for the deep sluggish Khausar, which protects the northern half of this face, then bends round towards the Tigris and flows through the middle of the town, so as to leave the south-east of the city more open to attack than any other part.

The principal ruin mounds within the walls are that of Kuyúnjik, north of the Khausar, and that of the prophet Jonah (Nebí Yúnus) south of that stream. The latter is the traditional site of Jonah’s preaching, and is crowned by an ancient and famous Mohammedan shrine. The systematic exploration of these ruins is mainly due to Layard (1845-46), whose work has been continued by subsequent diggers. These researches leave no doubt as to the correctness of the local tradition.

Not only have magnificent remains of Assyrian architecture and sculpture been laid bare, but the accompanying cuneiform inscriptions throw much light on the history of the city and its buildings. The mound of Kuyúnjik covers palaces of Sennacherib and Assurbanipal (Footnote 512-1), that of Jonah a second palace of Sennacherib and one of Esarhaddon. Of other remains, the most striking is the gateway near the center of the north wall, consisting of two halls, 70 feet by 23, the entrance to which towards the town was flanked by colossal man-headed bulls and winged human figures. For the structure and art of the palaces see vol. ii. p. 397 and vol. iii. p. 189.

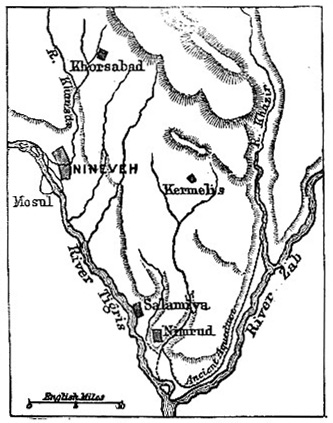

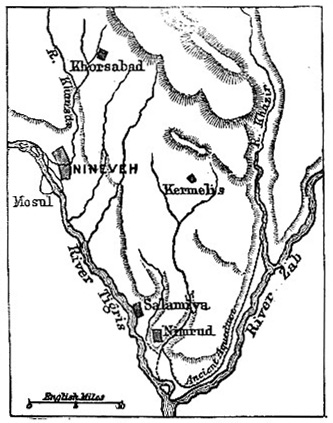

Nineveh proper was only one of a group of cities and royal residences whose ruins still mark the plain between the Tigris, the Great Záb, and the Kházir. The chief of these are at Khorsábád or Khurustábád, five hours by caravan north-east of Mosul, on a tributary of the Khausar, and at Nimrúd, on the left bank of the Tigirs, eight caravan hours (18 miles) south-east from Kuyúnjink. The former site was mainly explored by the Frenchmen Botta and Place. the city was almost square, each face of the wall a little more than a mile in length. The vast T-shaped palace of Sargon (722-705 B.C.), whose name the town bore (Dur-Sarrukin), stood near the northern angle. Its main frontage was nearly a quarter of a mile long; it had thirty-one courts and more than two hundred apartments.(Footnote 512-2)

Fig. 1 -- Country round Nineveh

The ruins of Nimrúd, identical with the ruin Athúr of Arabic geographers (Yákút, s.v.v., "Athúr," "Salámíya"), and first excavated by Layard, represent the ancient city of Kalhu, the Biblical Calah. The enclosure, protected on the west by the old bed of the Tigris, is, according to Layard’s measurements, a quadrangle of 2331 yards by 2095 at the widest part, and was surrounded by walls with towers and moats.

The chief architectural remains belong to a group of palaces and temples which occupied the south-west quarter of the city. The principal palace (north-west palace) was built by Assur-nasir-pal (885-860 B.C.), and beside it he raised a temple with a great tower (falsely called the tomb of Sardanapalus) built in narrowing stages. The so-called central palace is that of his son Shalmaneser II, the unfinished south-west palace was the work of Esarhaddon. Of the so-called south-east palace the chief part is really a temple of Nebo; a statue of the god from this temple is in the British Museum.

The main points in the history of these three great cities which are held to be established by monumental evidence are these. The ancient capital of Assyria was Assur (Kal’a Sherkát) on the Tigris, 50 miles south of Mosul. Assur-nasi pal transferred the residence to Calah, a city which he tells us upon an inscription had been originally founded by Shalmaneser I. (c. 1300 B.C.), but had subsequently fallen into decay.

Calah seems to have been the chief seat of the kings till Sargon the captor of Samaria founded his residence at Khorsábád; the glory of Nineveh proper begins with Sennacherib, but the city existed earlier, for his inscribed bricks represent him only as rebuilder of the walls. It is even averred that kings of the 19th and 15th centuries B.C. built temples at Nineveh, but the remoter dates of Assyrian history must be received with caution. (Footnote 512-3)

From the time of Sennacherib down to the fall of the capital and empire -- an event the date of which is still uncertain, the ancient accounts varying between 626 and 608 B.C. -- Nineveh proper, that is, the city of the Tigris and Khausar, appears to have been the chief seat of empire. But when the book of Jonah speaks of Nineveh as a city of three days’ journey, or when Ctesias in Diodorus ii. 3 describes its circuit as 480 stadia, it is plain that these conceptions imply an extension of the name to the whole group of cities between the Tigris and the Zab.

In this connection the words of Gen. x. 11 sq. are remarkable; for, on the most natural view, the clause "this is the great city" applies not to Resen alone but to the four cities of Nineveh, Rehobth Ir, Calah, and Resen. Rehoboth Ir and Resen are still untraced; the Syriac tradition which connects the latter with Resh 'Aina, that is, with Khorsábád, does not agree with the text, which says expressly that Resen was between Nineveh and Calah, and indeed the verses in Genesis appear to be older than the foundation of the city of Sargon. The description would suit the mound of Salámíya a little above Nimrúd, but in fact the whole district is studded with ruins.

Fig. 2 -- Ruins of Nineveh

See the works of Layard Botta and Glandin, V. Place, Opper (Expédition en Mésopotamie), and G. Smith (Assyrian Discoveries). For the ruins and their exploration, Tuch’s Commentatio, above cited, gives all that was known before the explorations., Schrader, Keilinsch. u. A. T. gives the bearing of recent discoveries on the Biblical records. See also, in general, the article BABYLONIA, vol. iii. p. 183 sq. ( W.R.S)

Footnotes

511-4 It is generally agreed, and the description hardly leaves a doubt, that the ruins of Mespila and Larissa described by Xenophon, Anab., iii. 4. 7 sq., are Kuyúnjik and Nimrúd respectively. In this case we can be certain that there was no inhabited city on the spot at the time of the march of the Greeks with Cyrus. Comp. Strabo xvi. p. 245.

511-5 The references collected by Tuch, De Nino Urbe, Leipsic [Leipzig], 1845, are copious but might easily be added to. Ibu Jubair, p. 237 sq., who as usual is pillaged by Ibn Batuta, ii. 137, gives a very good description of the ruins and of the great shrine of Jonah as they were in the 12th century. The name Ninawa was not appropriated to the ruins, but was applied to the Rustak (fields and hamlets) that stood on the site (Beláhorí, p. 331; Ibn Haukal, p. 145; Yákút, ii. 694).

511-6 A change in the bed of the stream has left a space between the wall and the present channel of the Tigris.

512-1 In this palace is the famous library chamber from which Layard and George Smith brought back the tablets now in the British Museum, containing the account of the deluge.

512-2 There is some evidence that Syriac tradition connected these ruins with the name of Sargon; though our authority Yárkút, in giving the alleged old name of Khursustábád, has corrupted Sarghún into Sar'ún, by writing ___ for ___. Another Syriac tradition connects Khurustabad with Resen, finding the name Resen in the neighbouring Rás al-'Ain (Resh 'Aina). See Hoffmann, Syrische Acten, p. 183.

512-3 The legend of Ninus and Semiramis in classical authors appears to be of late origin and quite unhistorical. Ninus is merely the eponym hero Nineveh

The above article was written by: William Robertson Smith, joint editor of the Ninth Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica; Professor of Oriental Languages and Old Testament Exegesis, Free Church College, Aberdeen, 1870-81; one of the Old Testament Revisers, 1875; Lord Almoner's Professor of Arabic at Cambridge, 1883; University Librarian, 1886; author of Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia and Lectures on the Religion of the Semites.

|