1902 Encyclopedia > Otter

Otter

OTTER, a group of animals belonging to the family Mustelidae, to the order Carnivora (see MAMMALIA, vol. xv. p. 439), distinguished from their allies by their aquatic habits. The true otters-constitute the genus Lutra of zoologists, of which the common species of the British isles, L. vulgaris, may be taken as the type. It has an elongated, low body, short limbs, short broad feet, with five toes on each, connected together by webs, and all with short, moderately strong, compressed, curved, pointed claws. Head rather small, broad, and flat; muzzle very broad; whiskers thick and strong; eyes small and black; ears short and rounded. Tail a little more than half the length of the body and head together, very broad and strong at the base, and gradually tapering to the end, somewhat flattened horizontally. The fur is of very fine quality, consisting of a short soft under fur of a whitish grey color, brown at the tips, interspersed with longer, stiffer, and thicker hairs, very shining, grayish at the base, bright rich brown at the points, especially on the upper parts and outer surface of the legs; the throat, cheeks, under parts and inner surface of the legs brownish grey throughout. Individual otters vary much in size. The total length form the nose to the end of the tail averages about 3 _ feet, of which the tail occupies 1 foot 3 or 4 inches. The weight of a full size male is from 18 to 24 lb, that of a female about 4 lb less.

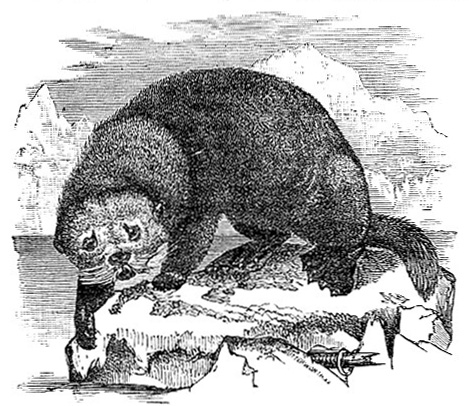

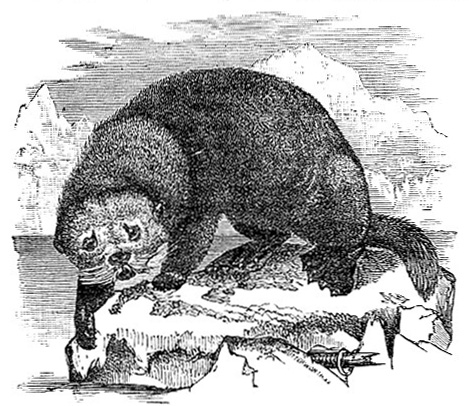

The Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris). From Wolf in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1865, pl. vii.

As the otter olives almost exclusively on fish, it is rarely met with far from water, and usually frequents the shores of brooks, rivers, lakes, and in some localities, the sea itself. It is a most expert swimmer and diver, easily over taking and seizing fish in the water, but when it has captured its prey it brings it to shore to devour it. When lying upon the bank it holds the fish between its fore-paws, commences at the head and then eats gradually towards the tail, which it is said always to leave. The female proceeds three to five young ones at a time, in the month of March or April, and brings them up in a nest formed of grass or other herbage, usually placed in a hollow place in the bank of a river, or under the shelter of the roots of some overhanging tree. The Common Otter is found in localities suitable to its habits throughout Great Britain and Ireland, though far less abundantly than formerly, for, being very destructive to fish, and thus coming into keen competition with those who pursue the occupation of fishing either for sport or for gain, it is rarely allowed to live in peace when once its haunts are discovered. Otter hunting with packs of hounds of a special breed, ad trained for the purpose, was formerly a common pastime in the country. When hunted down and brought to bay by the dogs, the otter is finally dispatched by long spears carried for the purpose by the huntsmen.

The Common Otter ranges throughout the greater part of Europe and Asia. A closely allied but larger species, L. Canadensis, is extensively distributed throughout North America, where it is systematically pursued by professional trappers for the value of its fur. An Indian species, L. nair, is regularly trained by the natives of some parts of Bengal to assist them in fishing, by driving the fish into the nets. Ion China also otters are taught to catch fish, being let into the water for the purpose attached to a long cord.

Otters are widely distributed over the earth, and, as they are much alike in size and coloration, their specific distinctions are by no means well defined. Besides those mentioned above, the following have been described, L. California, North America; L. felina, Central America, Peru, and Chili; L. brasiliensis, Brazil; L. maculicollis, South Africa; L. whiteleyi Japan; L. chinensis, China and Formosa, and other doubtful species. A very large species from Demerara and Surinam with a prominent flange-like ridge along each lateral margin of the tail, L. sandbachii, constitutes the genus Pteronura of Gray. Others, with the feet only slightly webbed, and the claws exceedingly small or altogether wanting on some of the toes, and also with some difference in dental characters, are with better reason separated into a distinct genus called Aonyx. These are A. inunguis from South Africa and A. leptonyx from Java and Sumatra

More distinct still is the Sea-Otter (Enhydra lutris). It differs from all other known Carnivora in having but two incisors on each side of the lower jaw, the one corresponding to the first (very small in the true otters) being constantly absent. Though the molar teeth resemble those of Lutra in their proportions, they differ very much in the exceeding roundness and massiveness of their crowns and bluntness of their cusps. The fore feet are very small, with five short webbed toes, and naked palms; the hind feet are altogether unlike those of the true otters, but approaching those of the seals, being large, flat, palmated, and furry on both sides. The outer toe is the largest and stoutest, the rest gradually diminishing in size to the first. The tail is about one-fourth of the length of the head and body, cylindrical and obtuse. The entire length of the animal from nose to end of tail is about 4 feet, so that the body is considerably larger and more massive than that of the english otter. The skin is peculiarly loose, and stretches when removed from the animal so as to give the idea of a still larger creature than it really is. The fur is remarkable for the preponderance of the beautifully soft woolly under fur, the longer stiffer hairs being very scanty. The general color is a deep liver-brown, everywhere silvered or frosted with the hoary tips of the longer stiff hairs. These are, however, removed when the skin is dressed for commercial purposes.

Sea-otters are only found upon the rocky shores of certain parts of the north Pacific Ocean, especially the Aleutian Island and Alaska, extending as far south on the American coast as Oregon; but owing to the unremitting persecution to which they are subjected for the sake of their skins which rank among the mot valuable known to the furrier, their numbers are greatly diminishing, and, unless some restriction can be placed upon their destruction, such as that which protects the fur seals of the Pribyloff Islands, the species is threatened with extermination, or, at all events, excessive scarcity. When this occurs, the occupation of five thousand of the half-civilized natives of Alaska, who are dependent upon sea-otter hunting as a means for obtaining their living, will be gone. The principal hunting grounds t present are the little rocky islets and reefs around the island of Saanach and the Chernobours, where they are captured by spearing, clubbing, or nets, and recently by the more destructive rifle bullet. They do not feed on fish, like the true otters, but on clams, mussels, sea-urchins, and crabs, and the female brings forth but a single young one at a time, apparently at no particular season of the year. They are excessively shy and wary, and all attempts to rear the young ones in captivity have hitherto failed.

See Elliott Coues, Monograph of North American Fur-bearing Animals, 1877. ( W. H. F.)

The above article was written by: Sir William Henry Flower, K.C.B., D.Sc, D.C.L., LL.D., Ph.D., F.R.S.; Director of British Museum, Natural History Department; President of the Zoological Society; President of the Britsh Association, 1889; author of Introduction to the Osteology of Mammalia and The Horse: a Study in Natural History.

|