1902 Encyclopedia > Mt. Vesuvius

Mt. Vesuvius

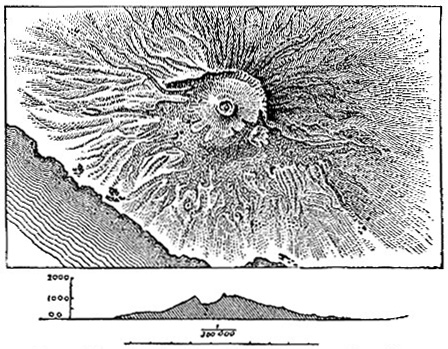

VESUVIUS, the most celebrated volcano in the world, rises from the eastern margin of the Bay of Naples in Italy, in the midst of a region which has been densely populated by a civilized community for more than twenty centuries. Hence it has served as a type for the general popular conception of a volcano, and its history has supplied a large part of the information on which geological theories of volcanic action have been based. The height of the mountain varies from time to time within limits of several hundred feet, according to the effects of successive eruptions, but averages somewhere about 4000 feet above the sea. Vesivius consists of two distinct portions. On the northern side of lofty semicircular cliff, reaching a height of 3747 feet, half encircles the resent active cone, and descends in long slopes towards the plains below. This precipice, known as Monte Somma, forms the wall of an ancient prehistoric crater of vastly greater size than that of the present volcano. The continuation of the same wall round its southern half has been in great measure obliterated by the operations of the modern vent, which has built a younger cone upon it, and is gradually filling up the hollow of the prehistoric crater. At the time of its greatest dimensions the volcano was perhaps twice as high as it is now. By a colossal eruption, of which no historical record remains, the upper half of the cone was blown away. It was around this truncated cone that the early Greek settlers founded their little colonies.

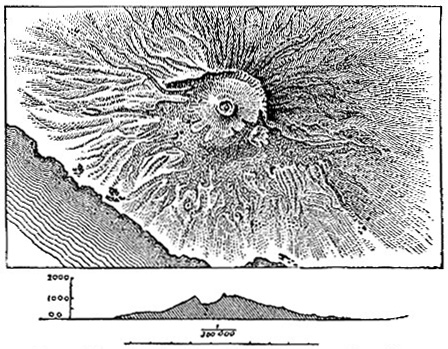

View of Mt Vesuvius (Vesuvio) and the Bay of Naples

At the beginning of the Christian era, and for many previous centuries, no eruption had been known to take place from the mountain, and the volcanic nature of the locality was perhaps not even suspected by the inhabitants who planted their vineyards along its fertile slopes, and built their numerous villages and towns around its base. The sagacious and observant geographer Strabo, however, detected the probable volcanic origin of the cone and drew attention to its cindery and evidently fire-eaten rocks. From his account and other references in classical authors we gather that in the first century of the Christian era, and probably for hundreds of years before that time, the sides of the mountain were richly cultivated, but towards the top the upward growth of vegetation had not concealed the loose ashes which still remained as evidence of the volcanic nature of the place. On this barren summit lay a wide flat depression, surrounded with rugged walls of rock, which were festooned with wild vines. The present crater-wall of Somma is doubtless a relic of that time. It was in this lofty rock-girt hollow that the gladiator Spartacus was besieged by the prater Claudius Pulcher, and from which he escaped by twisting ropes of vine-branches and descending through an unguarded notch in the crater-rim.

After centuries of quiescence the volcanic energy began again to manifest itself in a succession of earthquakes, which spread alarm far and wide through Campania. For some sixteen years after 63 these convulsions continued, doing much damage to the surrounding towns. At Pompeii, for example, among other devastation, the temple of Isis was shaken into ruins, and, as an inscription records, it was rebuilt from the foundation by the munificence of a private citizen. This preliminary earthquake phase of volcanic excitement was succeeded by a catastrophe which stands out prominently as one of the great calamities of human history. On 24th August 79 the earthquakes, which had been growing more violent, culminated in a tremendous explosion of Vesuvius. A contemporary account of this event has been preserved in two letters of the younger Pliny to the historian Tacitus. From this narrative we can gather a tolerably clear conception of the general characteristics of the eruption: abundant and increasingly violent earthquakes, followed by an extraordinary commotion that accompanied the outburst of the volcano, when chariots would not remain still even on level ground, when houses were shaken so as to threaten destruction to their inhabitants, and when the unsteadiness of the land gave rise to great disturbance of the sea, which in its agitation retreated from the shores and left numerous marine animals uncovered; the well-known pine-tree-shaped cloud of steam, dust, and stones towering above Vesuvius and spreading out far and wide over the surrounding country; the constant flashes of lightning marking the highly electrical condition of the column of erupted material; the showers of light cinders and ashes that fell at a distance from the mountain and the rain of hot pumice and pieces of black or glowing lava around the center of eruption; the total darkness for three days produced by the diffusion of the finer volcanic dust through the atmosphere; the fiery glare that overspread the cloud canopy as each explosion uncovered the glowing surface of the lava column in the chimney of the volcano; and the wide covering of ashes, which like a mantle of snow was found to have been spread over the surrounding country when the darkness cleared away and the catastrophe came to an end. This eruption was attended with great destruction of life and property. Three towns are known to have been destroyed -- Herculaneum at the western base of the volcano, Pompeii on the south-east side, and Stabiae, still farther south on the site of the modern Castellamare. The exhumation of Herculaneum and Pompeii in modern times has thrown much light upon the life of Roman citizens in the first century. There is no evidence that any lava was emitted during this eruption. But the abundant steam given off by the volcano seems to have condensed into copious rain, which mixing with the light volcanic dust, gave rise to torrents of pasty mud, that flowed down the slopes and overwhelmed houses and villages. Herculaneum is believed to have been destroyed by these "water lavas," and there is reason to suppose that similar materials filled the cellars and lower parts of Pompeii. Comparing the statements of Pliny with the facts still observable in the district, we perceive that this first recorded eruption of Vesuvius belongs to that phase of volcanic action known as the paroxysmal, when, after a longer or shorter period of comparative tranquillity, a volcano rapidly resumes its energy and the partially filled-up crater is cleared out by a succession of tremendous explosions. The great eruption of Krakatoa in the Sunda Strait in 1883 is a recent example of the same stage in the history of a volcano.

Map of Mt Vesuvius, together with north-and-south profile

For nearly fifteen hundred years after the catastrophe of 79 Vesuvius remained in a condition of feeble activity. Occasional eruptions are mentioned, but none that was of importance, and their details are given with great vagueness by the authors who allude to them. By the end of the 17th century the mountain had resumed much the same general aspect as it presented before the eruption described by Pliny. Its crater walls, some 5 miles in circumference, were hung with trees and brushwood, and at their base stretched a wide grassy plain, on which cattle grazed and where the wild boar lurked in the thickets. The central tract was a lower plain, covered with loose ashes and marked by a few pools of hot and saline water. At length, after a series of earthquakes lasting for six months and gradually increasing in violence, the volcano burst into renewal paroxysmal activity on 16th December 1631. Vast clouds of dust and stones, blown out of the crater and funnel of the volcano, were hurled into the air and carried for hundreds of miles, the finer particles falling to the earth even in the Adriatic and at Constantinople. The clouds of steam condensed into copious torrents, which, mingling with the fine ashes, produced muddy streams that swept far and wide over the plains, reaching even to the foot of the Apennines. Issuing from the flanks of the mountain, several streams of lava flowed down towards the west and south, and reached the sea at twelve or thirteen different points. Though the inhabitants had been warned by the earlier convulsions of the mountain, so swiftly did destruction come upon them that 18,000 are said to have lost their lives.

Since this great convulsion, which emptied the crater, Vesuvius has never again relapsed into a condition of total quiescence. At intervals, varying from a few weeks or months to a few years, it has broken out into eruption, sometimes emitting only steam, dust, and scoriae, but frequently also streams of lava. The years 1766-67, 1779, 1794, and 1822 were marked by special activity, and the phenomena observed on each of these occasions have been fully described.

The modern cone of the mountain has been built up by successive discharges of lava and fragmentary materials round a vent of eruption, which lies a little south of the center of the prehistoric crater. The southern segment of the ancient cone, answering to the semicircular wall of Somma on the north side, has been almost concealed, but is still traceable among the younger accumulations. The numerous deep ravines that indented the sides of the pre-historic volcano, and which still form so marked a feature on the outer slopes of Somma, have on the south side served as channels to guide the currents of lava from the younger cone. But they are gradually being filled up there and will before long disappear under the sheets of molten rock that from time to time rush into them from above. On one of the ridges between these radiating valleys an observatory for watching the progress of the volcano was established many years ago by the Neapolitan Government, and is still supported as a national institution. A continuous record of each phase in the volcanic changes has been taken, and some progress has been made in the study of the phenomena of Vesuvius, and in prognosticating the occurrence and probable intensity of eruptions. A wire-rope railway (opened in the year 1880) carries visitors from the foot of the cone up to within 150 yards of the mouth of the crater.

See Volcanoes, by G. P. Scrope, 1872; Vesuvius, by John Phillips, 1869; Der Ausbruch des Vesuv in April 1872, by A. Heim, 1873; Vesuvio e la sua Storia and Pompeii e la Regione Sotterrata dal Vesuvio nel’ Anno 79, by Prof. Palmier, Naples, 1879; Studien über Vulkane und Erdbeben, by J.J.F. Schmidt, 1881; and "The Geology of Monte Somma and Vesuvius," H. J. Johnstone-Lavis, 1884, in Quart, Journ. Geol. Soc., vol. xl. P. 85 See also GEOLOGY, vol. x. p. 240 sq. ( A. GE.).

The above article was written by Sir Archibald Geikie, D.C.L., D.Sc., LL.D., F.R.S; Director, Geological Survey of Scotland, 1867; first Murchison Professor of Geology and Mineralogy, Edinburgh, 1871-82; Foreign Secretary, Royal Society, 1890-94; President, Geological Society1891-92; President, British Association, 1892; Director-General, Geological Survey of United Kingdom, and Director, Museum of Practical Geology, 1882-1901; author of The Scenery of Scotland, viewed in connection with its Physical Geology; New Geological Map of Scotland; The Ancient Volcanoes of Britain; etc.

|